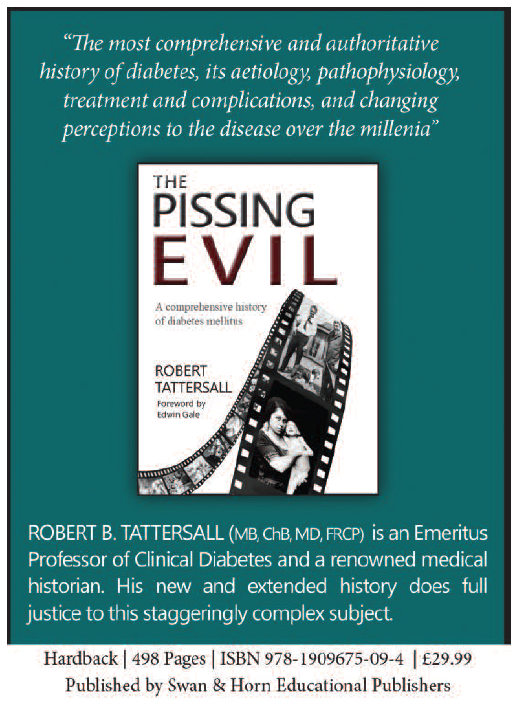

Title: The Pissing Evil, A Comprehensive History of Diabetes

Author: Robert Tattersall

Publisher: Swan & Horn, 2017

ISBN: 978-1909675-09-4

This old erudite and delightful earlier professor in medicine has now ... given us a sensationally well-written intelligent [history of diabetes]”. The slightly modified quotation included in the book referred to a post-retirement literary contribution by a former eminent diabetologist, Knud Lundbaek of diabetic angiopathy fame. There are obvious parallels with The Pissing Evil. Robert Tattersall had a glittering career as a diabetologist, clinical researcher and medical editor, inspired a generation of clinicians, and after retiring from practice has devoted himself to researching and writing about the history of his specialty.

The book's title, The Pissing Evil, taken from Thomas Willis's 17th century discourse on diabetes, may consign it to the top shelf of the book case rather than the coffee table in homes inhabited by young children. If you can get past that, you will find the book lives up to its billing as 'the most complete history of diabetes ever written'. Tattersall takes us on a journey through time from Ancient Egypt to the recent past, explaining what was understood about diabetes in different historical periods and how modern understanding of the condition(s) depended on the curiosity, determination, skill and sometimes good fortune of an army of men and women named on a 44-page honours board at the end of the book. He cannot resist slipping in biographical anecdotes about these heroes and villains of diabetes, which this reviewer enjoyed, but others may find distracting. The inclusion of transcripts from interviews with people who have lived with diabetes for many years helps the reader appreciate what it was like to be on the receiving end of treatments and diets that changed with time.

Some might think he has occasionally missed the chance to relate historical themes to the present day, most notably von Mering's description of phloridzin glycosuria to the use of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors to treat type 2 diabetes. The acknowledgment that self blood glucose monitoring, for which Tattersall shared the credit, cannot be the end of the diabetes monitoring story is not linked to the introduction of flash and continuous glucose monitoring.

I particularly enjoyed the account of the University Group Diabetes Program (UGDP) trial of treatments for non-insulin dependent diabetes, a well-intentioned but poorly-conducted study, the fall-out from which gave birth to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study, the brainchild of Robert Turner who, according to Tattersall, wrote his body weight in grant applications to fund it. This reviewer had not appreciated that the results of the UGDP trial had been leaked to the press before publication, causing the share price of certain pharmaceutical companies to collapse. Today's investors are no less interested in the cardiovascular outcome trials of new to market diabetes drugs.

There are gems to be discovered throughout the book. I was thrilled to read Kussmaul's own description of his eponymous respiration that characterises diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). The discovery of insulin is a chapter in itself; the simplified (and wrong) version has been painstakingly dissected and the record set as straight as it is ever likely to be. Readers will have to decide for themselves whether the Nobel Prize committee got it right.

The management of DKA in 16–18-year-olds is a controversial topic in the UK at the moment, so this reviewer looked for enlightenment in the chapter on ‘Diabetic Coma and Ketoacidosis’. Tattersall mentions two papers from the 1960s describing five patients aged 9–16 years who developed cerebral oedema, and the subsequent description by Clements et al in 1971 of changes in cerebrospinal fluid pressure during treatment of DKA.

Oddly, the book stops abruptly with a final chapter on ‘Miscellaneous Complications’. This reviewer was expecting a brief reflective conclusion, but perhaps to end as it does with a description of one of Tattersall's own cases is sufficient and appropriate.

This book will be a rewarding read for healthcare professionals and researchers in diabetes, and provides a rich supply of anecdotes for consultant ward rounds.

Robert Gregory

Consultant Physician, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, Leicester, UK.

E-mail: rob.gregory@uhl-tr.nhs.uk